Image: Shutterstock

The Ontario Superior Court has ruled it has jurisdiction to hear the case against ChatGPT owner OpenAI brought by a consortium of Canadian media companies led by the Toronto Star. The media enterprises, who include the Globe and Mail, PostMedia, CBC/Radio Canada, Canadian Press and Metroland Media Group, are suing the US company for copyright infringement, circumvention of technological protection measures (TPMs), breach of contract, and unjust enrichment as a result of OpenAI’s scraping of their websites to obtain content to train its AI algorithm. The allegations also cover OpenAI’s use of Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) to produce contemporary search results from paywall-protected content that augment ChatGPT’s AI-generated responses. When the suit was brought in November 2024, OpenAI had challenged the Ontario court’s jurisdiction on the basis, among others, that it had no physical presence in Canada. As pointed out by this legal blog, a court may presumptively assume jurisdiction over a dispute where one of five factors is present:

- The defendant is domiciled or resident in the province.

- The defendant carries on business in the province.

- The tort was committed in the province.

- A contract connected with the dispute was made in the province.

- Property related to the asserted claims is located in the province.

The court found that OpenAI carries on business in Ontario notwithstanding its lack of a physical presence and was a party to contracts in Ontario as a result of tacitly accepting the terms of service regarding access to the media companies websites when it scraped them.

OpenAI wanted the venue of the litigation changed to the United States to take advantage of developments in US law regarding unauthorized reproduction of copyright protected content for use as AI training inputs. To date, while many cases are still ongoing, US courts have tended to support a fair use argument by AI developers allowing them to access copyrighted content without permission on the basis that the end use is “transformational”, resulting in a new product that does not compete with the original work. In Canada, the fair use doctrine does not apply and exceptions to copyright protection are either explicitly laid out in the law (e.g. for law enforcement or archival preservation purposes) or are governed by the fair dealing provisions of the Copyright Act. These require that an unauthorized use fall into one of eight categories (research, private study, education, parody, satire, criticism, review and news reporting) that is in turn subject to various court-interpreted criteria such as amount of the work copied, the purpose of the copying, market impact etc. AI developers have been lobbying for the introduction of a text and data mining (TDM) exception into Canadian copyright law, but so far this has been successfully resisted by Canada’s creative community. All this to say that it is more difficult for AI companies to avoid liability for unauthorized use of copyright protected material in Canada than in the US, thus the importance of whether the Ontario court has jurisdiction.

Back in September, on the basis of previous Canadian court rulings where courts ranging from provincial courts to the Supreme Court of Canada asserted jurisdiction over large digital US companies operating virtually in Canada, such as Google (who challenged Canadian legal authority over them on the basis of lack of a physical presence), I predicted (guessed would be a more accurate term) that the Ontario court would be loath to surrender jurisdiction simply because the company was headquartered in the US. The earlier cases were for defamation rather than copyright infringement, and my “prediction” was based more on a hunch than legal analysis, but I am satisfied that I called it right. OpenAI has no compunction about selling services and collecting revenues in Canada and presumably (I hope) pays taxes here, although it is not subject to the Digital Services Tax (DST) that the Carney government threw overboard in a vain attempt to placate Donald Trump. Recall that Trump had threatened to terminate trade talks if Canada proceeded to implement the long-planned DST, so Canada blinked. Trade talks resumed until Trump found another excuse to end the talks, in this case the anti-tariff ads on US television placed and paid for by the Ontario government to which he took offence. But there is no doubt that OpenAI does business here; it just doesn’t want to be subject to Canadian law and Canadian courts. It can’t have it both ways.

While this is a victory for Canadian sovereignty, just because the Ontario Superior Court has confirmed its jurisdiction, this doesn’t mean that once the substantive proceedings begin copyright infringement will be found. Lawyer Barry Sookman, in an analytical blog post on this topic, has noted that in determining whether the alleged copyright infringements occurred in Canada, “the court relied heavily on the Supreme Court decision in SOCAN for the proposition that the territorial jurisdiction of the CCA (Canadian Copyright Act) extended to where Canada is the country of transmission or reception.” However, “SOCAN applied the real and substantial connection test to the communication to the public right” whereas the alleged copying involved the right of reproduction.

Sookman continues;

“…that test does not apply to the reproduction right. (The Federal Court has) held that the only relevant factor is the location in which copies of a work are fixed into some material form. The locations where source copies reside or acts of copying onto servers located outside of Canada, are not infringements” (according to the cases cited).

Inside baseball information but important when it comes to determining copyright infringement. On the other hand, it seems to me that the infringement involved not just, potentially, the reproduction right (the copying) but also the communication right, because OpenAI, through Microsoft, provided RAG content to users in Canada and elsewhere purloined from behind the paywalls of the media companies. So, we will have to see. Lots of fodder for IP lawyers.

In the meantime, deep-pocketed OpenAI will appeal the jurisdictional ruling—and will likely lose again. The appeal will buy time for it to negotiate licensing deals with the complainants. This is increasingly the model in the US as AI developers, including OpenAI, are reaching licensing agreements with content owners, particularly media organizations. To date, OpenAI has signed licensing deals with the Associated Press, the Atlantic, Financial Times, News Corp, Vox Media, Business Insider, People, and Better Homes & Gardens, among others, while being sued (in addition to Toronto Star et al), by the New York Times and a collection of daily newspapers consisting of the New York Daily News, the Chicago Tribune, the Orlando Sentinel, the Sun Sentinel of Florida, San Jose Mercury News, The Denver Post, the Orange County Register and the St. Paul Pioneer Press. Even META, that arch-opponent of paying for media content–which it claims adds no value to its users– has struck a media deal with news publishers, including USA Today, People, CNN, Fox News, The Daily Caller, Washington Examiner and Le Monde. (One wonders if this will cause it to rethink its position of thumbing its nose at Canada’s Online News Act, where it “complied” with the legislation by blocking all Canadian news links).

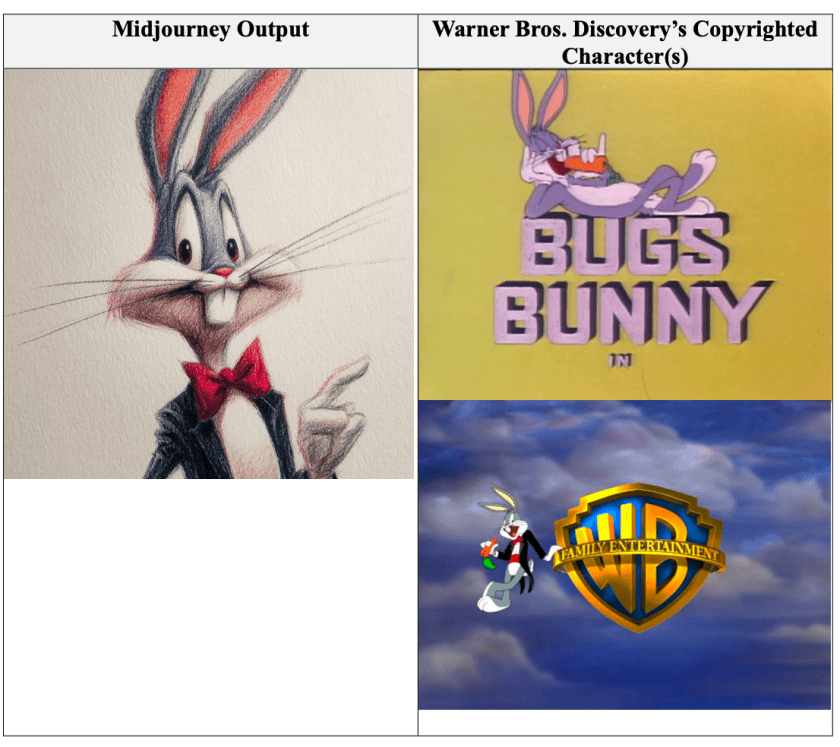

In another content area, OpenAI and Disney have just agreed on a three-year output deal, allowing it to use Disney characters (subject to certain limitations) in its AI creations. (Meanwhile Disney is suing Google for using its characters in Google’s AI offering). Open AI is currently facing 20 lawsuits, including the Toronto Star case, and needs to resolve these legal challenges before its expected public offering next year or 2027. The spectre of impending lawsuits will inevitably lower the IPO price.

Most if not all of these lawsuits are going to end in settlements via voluntary licensing agreements, but that will only happen if OpenAI thinks the alternative (losing a major lawsuit) is a worse outcome. If it can wriggle out from the Toronto Star case by invoking some specious argument related to jurisdiction, it will. If it can’t it, will eventually open its chequebook and provide the Canadian media outlets some compensation for the valuable curated content it has hijacked. Canadian courts need to stay the course to help ensure that this happens.

© Hugh Stephens, 2025. All Rights Reserved.