Canada Has a Choice When it Comes to AI Training Content

Michael Geist, Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-Commerce Law at the University of Ottawa has argued, in an appearance before the Heritage Committee of the House of Commons, that “we need more Canada in the training data”. He is absolutely right, but just not in the way he proposes. Dr. Geist is what I would call a well-known skeptic when it comes to the intrinsic value of copyright, a copyright “minimalist” if you will (probably an understatement).

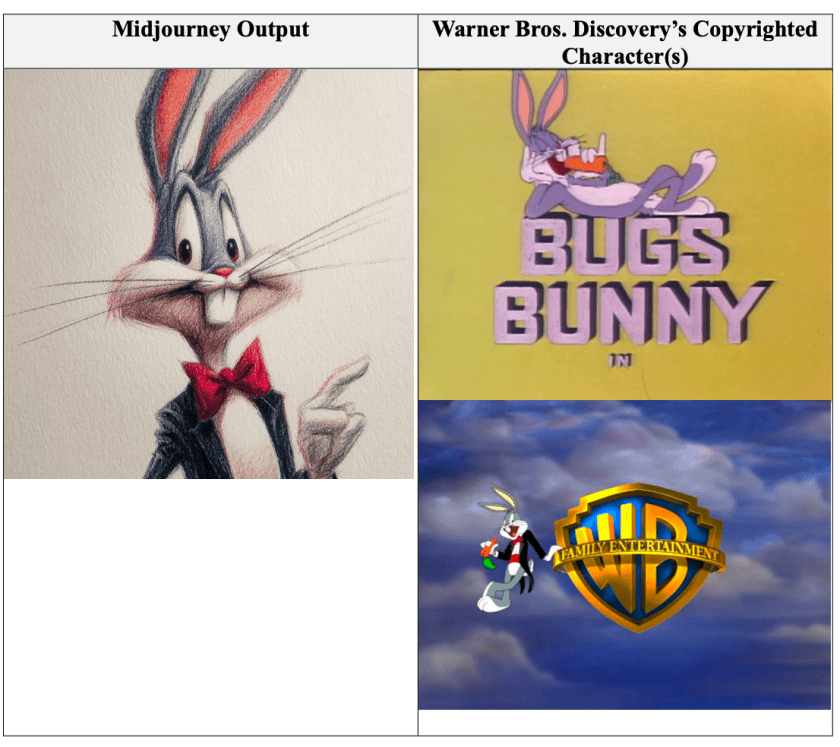

With respect to the unauthorized and uncompensated use of copyrighted content for AI training, he states that “in the context of AI, the application of copyright isn’t clear cut. The outputs of AI systems rarely rise (to) the level of actual infringement given that the expression may be similar or inspired by another source, but it is not a direct copy of the original.” Whether the outputs mirror the inputs is not the sole issue. In some cases, such as when music and images have provided the inputs, they do. This is an infringement of the reproduction right, and likely also an infringement of the distribution right and the right to produce a derivative copy (under US law). In Canada the right to create another work from an original work comes from the right of adaptation. However, even without a mirrored output, full reproduction still takes place at the input stage, creating an infringement unless the copies meet a fair dealing purpose and fulfill fair dealing criteria, even if the copies are later deleted. As Keith Kupferschmid, CEO of the Washington DC based Copyright Alliance has pointed out in a recent blog post discussing the copyright principles that apply in AI training cases,

“Some people mistakenly believe that in order to establish an infringement during the input stage, the copyright owner needs to establish substantial similarity between the ingested copyrighted work and AI-generated output and if no substantial similarity exists there is no infringement in this stage. That is incorrect.”

Even without mirrored outputs, full non-transitory copies of copyrighted works are being made at the ingestion stage of AI training. That is an infringement, just as making a photocopy of a complete work, such as a book, would be an infringement unless covered by an explicit exception such as preservation purposes by a library or archive.

Dr. Geist’s second line of argument is that if Canada makes it more difficult or costly to develop large language models, AI development will shift outside the country. This is a tried-and-true but tired pretext frequently employed by those seeking to justify the appropriation of copyright protected content in the name of “innovation”, as I pointed out in an earlier blog post. (CanLII v CasewayAI: Defendant Trots Out AI Industry’s Misinformation and Scare Tactics -But Don’t Panic, Canada). This is a race to the bottom, throwing the content industry under the bus on the pretext that everyone is doing it, even though that is untrue. One provision that has been selectively incorporated into the laws of some jurisdictions, like the UK and the EU, is an exception for “text and data mining” (TDM). Dr. Geist states this is why Canada also needs to introduce a similar statutory exception to promote AI.

However, not everyone is engaged in this race to the bottom. In fact, there are increasing doubts that establishing a statutory TDM exception for AI training is the best way to go. Australia has just firmly rejected the creation of a TDM exception in its copyright law even though it is also grappling with the same issue of how to incentivize AI training and research in that country. The UK’s current TDM exception is limited to non-commercial research purposes and in the face of strong opposition from its creative sector, Britain has put proposals to expand TDM on hold. Even the EU’s TDM law, which has two aspects, one limiting the data mining to non-commercial scientific research conducted by scientific research organizations or cultural heritage institutions while the other is a general purpose TDM that is open to commercial organizations, has guardrails. These include an opt-out provision whereby rightsholders can block ingestion of their content through technical measures, contract provisions or other means, in which case the TDM exception does not apply.

While opting-out by rightsholders is one way to limit the damage of unrestricted text and data mining, this is controversial because it places the onus on the rightsholder to take action whereas normally a party wanting to use someone else’s property would have to obtain permission in advance. Opting out is not a preferred solution for the creative community. It doesn’t work well in practice as rightsholders often lack the technical means or awareness to apply their opt-out rights. Because of this, the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs has just published a study examining how generative artificial intelligence interacts with European Union copyright law. The study recommends moving from opt-out to opt-in for rightsholders.

Thus, far from TDM being or becoming the norm, it is being rejected or constrained in a number of countries where the AI industry has been pushing it as the ultimate solution. The Canadian creative community, like the creative sector in Australia, has spoken out strongly against introducing a TDM exception into Canadian law. Indeed, there is no need to do so as licensing solutions allowing AI training and text and data mining are becoming more and more common, including in Canada. For example, the Writers Union of Canada is studying a proposed agreement between select nonfiction authors, HarperCollins, and Microsoft to license full texts for the purpose of training artificial intelligence. Licensing agreements have taken off big-time in the US and elsewhere as the AI industry begins to understand this is the safest way to protect their investments. Canadian creators risk being left by the roadside if Canada brings in a TDM exception that would allow AI developers to steam ahead, appropriating content without payment or permission and ignoring licensing requirements by hiding behind a TDM exception. The surest way to kill a nascent and growing licensing market is to give the AI sector a TDM loophole to exploit, removing any incentive to reach licensing agreements with rightsholders. The solution is licensing, not loopholes.

Dr. Geist stated in his testimony to the Heritage Committee that AI developers would take the view that if they had to pay for (i.e. to license) content from Canadian creators, they would simply exclude it. The record of licensing deals being reached elsewhere suggests this is completely off base. Instead, the record shows that when AI developers want reliable, curated content to make their product better than the competition, they are ready to pay for it. But they will never pay for it if they are given a blank cheque through a legislated loophole. He also claims the position of the creative community is “Don’t use my stuff”. Again, the record of licensing deals to date and in the pipeline disproves this characterization in spades. Rather than blocking use of their content, creators are saying, “If you want to use my content, let’s talk”. Finally, Dr. Geist managed to completely mischaracterize the position of the creative community with regard to licensing. He said in his testimony that creators are advocating for a change to copyright law to mandate payments for AI training use. On the contrary, the creative community is simply asking that existing copyright law not be gutted. There is no need to create a mandatory payment requirement; existing copyright law is fit for purpose in dealing with how those wishing to use copyrighted content for purposes that fall outside fair dealing can do so. Negotiate a licence.

If any proof is needed of how the creation of a loophole will kill a licensing market is, all one needs to do is look at the sorry state of educational publishing in Canada. The industry has been decimated, and many authors have lost their livelihood because of the ill-conceived educational exception that was introduced into Canada’s Copyright Act in 2012. With that loophole in place, educational institutions across the country, with the notable exception of Quebec, began to tear up the reproduction licenses they had held from Access Copyright, the copyright collective representing authors. The educational exemption as part of fair dealing criteria could still be fixed, but the educational sector, facing severe financial pressures, has a powerful lobby working against it. The financial pressures are real, but taking a free ride on educational publishers and authors is wrong.

What happened with educational publishing is a cautionary tale for Canada. It should not make the same mistake twice. The way to promote a strong AI industry, alongside vibrant content industries, is licensing, not loopholes. Building a robust AI/TDM licensing market is the way to get more Canada into the training data, not giving the AI industry a blank cheque to help itself to the proprietorial content of others. With voluntary licensing everyone benefits. AI developers get secure access to quality content; the creative sector is rewarded for its efforts and becomes a partner in developing responsible AI. It’s a shame that the Canada Research Chair at the University of Ottawa doesn’t understand this.

© Hugh Stephens, 2025. All Rights Reserved.